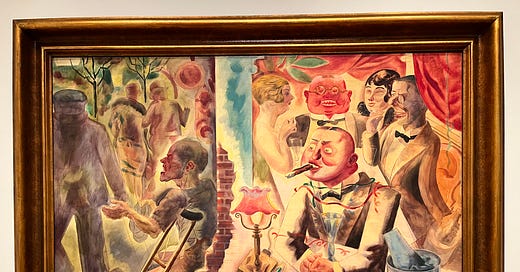

The early 20th century brought many emotional, turbulent, and critiquing art movements. George Grosz, originally Georg Ehrenfried Groß, was a prominent German artist known for his caricature portrayal of Berlin life and being one of the founders of the Berlin Dada movement. In Grosz’s oil painting Drinnen und Draussen (1926), which translates to Inside and Outside, he examines the growing wealth disparity of German society.

On the left, the lower class is represented with muted colors. It features little line work in a manner that gives the painting a washed-out watercolor look. On the right side, the upper class has more defined lines and visible features with bright, vibrant colors. A literal brick wall divides the two.

Grosz was influenced by the expressionist and futurist movement as well as children’s books. Expressionism, also originating from Germany, sprouted from the anxieties of modern life. Their angsty and emotional work uses distorted images with jarring colors. Futurism, on the other hand, originated in Italy, and it embraces modernity, even praising the technology, machinery, and war birthed by the modernization of society. Many artists from the time wished to eradicate tradition. Thus, faceted shapes and broken times are the distinct features of the futurist movement.

Dadaism, arguably a mash of both movements, has a more nihilistic approach, often questioning the purpose of art and artists. It emerged as a reaction to the horrors and atrocities of World War I and criticized the materialism of the bourgeois and the brute-ness of nationalism. Dada artists like Grosz liked to use heavily satirical and deliberately exaggerated figures for shock value, rejecting previous artistic values.

Grosz is defined for his work like Drinnen und Draussen. Businessmen, soldiers, and prostitutes are reoccurring subjects in his paintings, as he uses them to mock the bourgeoisie and supporters of the Weimar Republic. Drinnen und Draussen appears to have all three subjects. The angry beggar on the left is thin but muscular and has an amputated foot, indicating that he is a war veteran. The men in suits on the right, bloated and flushed from drinking, are flanked by two beautiful women (perhaps prostitutes?).

Interestingly, Grosz changed his original name, Georg Ehrenfried Groß, to George, the American spelling, and Gro[sz], the phonetic spelling, in a protest against German nationalism and enthusiasm for America and the “American dream.” Doing so also allowed him to internationalize his name to fit a world market better.

In 1933, he immigrated to the US. After moving, he seemingly lost most of his previous cynical and caricatural style. In the US, despite receiving some attention at The Museum of Modern Art, Grosz generally struggled to sell his paintings, so he began teaching at schools like Columbia University, Des Moines Art Center, and more. His post-immigration artwork, seen as the decline of his career, consists mainly of landscape watercolors and conventional nudes that hold more sentimental and romantic characteristics. That being said, during his time in America, he became depressed and developed alcoholism.

Grosz did move back to Berlin in 1959. Ironically, he died heavily intoxicated two months later after falling down a flight of stairs.

“I myself was everybody I drew, the rich man favored by fate, stuffing himself and guzzling champagne, as much as the one who stood outside in the pouring rain holding out his hand. I was, as it were, divided into two.” - George Grosz

His satirical and politically charged art penetrated the political scene in not only Berlin but also Russia and the rest of Europe, inspiring many artists and art movements that followed. Drinnen und Draussen can currently be seen at The Yale University Art Gallery as part of their Modern and Contemporary Art exhibit.